Angkor Wat: An International Wonder

Angkor Wat is an extremely special place - similar to Machu Picchu or Teotihuacan in how you can feel the history and the sophistication of the society that lived there. However, it is substantially larger than any other complex I’ve visited. It is still the largest religious monument in the world, sitting on 400+ acres of land - and you need to take tuk-tuks to get between the different sites!

Angkor Wat is a Buddhist temple, and historically it was the temple in the capital city of the Khmer Empire, Cambodia’s historical empire. It was founded in the 12th century and at its height was home to over 1 million people. At the time, was the most populated city in the world.

I found it absolutely incredible and learned a ton about the site before going, continued to listen to podcasts while there, and we went on a historical tour. As a history and museum nerd, I was all in!

A Rise and Fall Through Water Infrastructure

The Khmer Empire’s society was based on a selection of ties between different social classes. It was a structure of duty. Everyone - even the king - had a duty or tie to someone. The king had a duty to rule and provide their people with a living, to serve them. This included feeding them, protecting them, and taking care of them generally.

The king who built Angkor Wat was King Suryavarman II, from 1122 - 1150 CE. He was a Hindu king, ruling a Buddhist population. He built Angkor Wat as a Hindu temple. Special prayer areas were reserved for the royals and religious elite, others for the normal people. Most areas had three staircases: with the central one reserved for the elites. Everyone else had to use the side staircases with lower doors (forcing them to literally bow to the gods and kings as they ascended and descended the stairs).

When building Angkor Wat, he also moved the capital city of the emerging Khmer Empire to the area. Over time, the entire area developed into an urban complex. A major component of this was well-engineered water reservoirs, collecting vast amounts of water during the wet season to irrigate crops and provide drinking water during the dry season. With the city neighborhoods, which grew organically, fields were set up that were fully connected to these reservoirs, meaning food growth and access for the dry seasons. These were well maintained and expanded at the beginning of the empire and the city’s growth.

Over time, the city expanded - both by population and state-run building projects. It meant good food sources, access to culture and religious centers, and jobs. The area grew to have a population of 1,000,000 people in the 12th Century - the largest on Earth at the time.

The ruling class was generally Hindu, building Hindu temples - causing some tension with the population at times. The everyday person was Buddhist, and these people built Buddhist temples also. However, during the Khmer Empire, several kings converted to Buddhism and built temples for Buddhist practices. There is one temple that even combines Buddhism and Hindu architecture.

As the city grew, interests in where to spend money shifted. Over time, that interest in maintaining the complex water infrastructure fell by the wayside. Slowly the water systems and high-quality water supply diminished and were not invested in for repair. In the dry months, people found it harder and hard to live in the city and felt neglected by their leaders. Remember, everyone was serving someone - so the king had a duty to serve his people with water. Yet, many kings were not doing that.

Over several hundred years, people slowly (then quickly) migrated back to rural areas and left the city by choice because of where they saw their best opportunity to live. The city infrastructure continued to crumble until it fell under its own weight and eventually was almost abandoned altogether. Only Buddhists monks would visit and live there, keeping the sacred role of these Buddhist temples alive. Even as the buildings crumbled and literally fell over into piles of blocks around them, the Buddhist monks stayed true to their religion - generation and generation. I found this truly incredible.

Over time, everyone kind of forgot about the city and its history. It was just generally referred to as “the temple city” where monks live. In fact, “Angkor Wat” literally translates to “temple city” in the Khmer language (spoken in Cambodia). This is not the actual name that people living there had called it. We still do not know the name this vast and powerful city was called by its own people. It has become a “forgotten city” in many ways.

Angkor Wat - A Place of Local Pride

As you walk around the Angkor Wat Archeological Complex on a weekend, you see loads of Cambodians. There is a tourist ticket to see the complex, but it is free to Cambodian nationals - which we loved!

There is a palatable sense of national pride surrounding the Angkor Wat complex, even with Angkor Wat itself as the major symbol on the Cambodian flag. Locals use it as a place to gather and picnic. Multi-generational Cambodian families will arrive in matching outfits, from the 3-year-old to grandma, and take family photos with a photographer. You see engagement photos and people just walking around and taking in their own history with pride. It is incredible and so fun to watch.

It was one of the few places that I’ve been where a large archeological site is actually filled with the people who are ancestors of those who built it - and that they are enjoying it (not just guiding or selling or working there). You don’t see that in many places, but Cambodia has that. There are plenty of other freedoms that Cambodians do not have - especially right now as an authoritarian one-party government - but they do ensure their citizens can visit this place.

It was incredible to watch and heartwarming to see these families taking photos. It actually inspired us to do a photo session in matching clothes ourselves - and we will share those photos in a separate post!

Angkor Wat - Some Misnomers

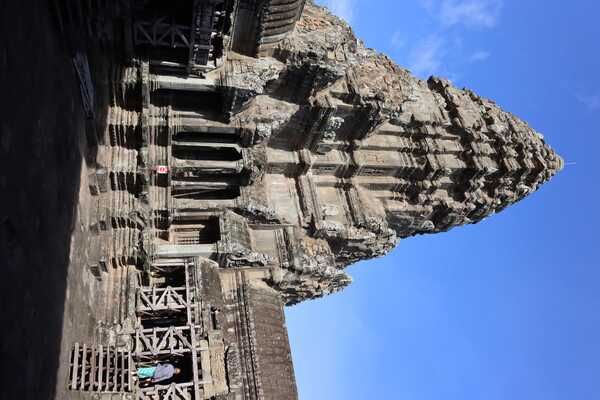

Angkor Wat, the famous building you see in all the photos, was a central religious temple. There are a couple of common misnomers and misconceptions about it, which I was fascinated to learn more about.

Many people mistakenly think of Angkor Wat as the center of the city - but that’s only partially true. Think of Angkor Wat as the Sistine Chapel - a massive building that exemplifies a commitment to religious faith while showing off wealth and prosperity. Of course, as a religious society, both buildings serve as a major heartbeat of their cities - but they are not office buildings or marketplaces, they are sacred religious spaces. Now, imagine if the rest of Vatican City and Rome were in a jungle area where trees and plants quickly reclaimed land. It could not even sit for one year without maintenance before nature started taking it back. Angkor Wat Archeological Complex and the surrounding area were abandoned for 800 years before being reconstructed through archeological efforts. The Angkor Wat building itself is the remaining Sistine Chapel. It is the remainder of the central religious temple, not the entire city. And the different temples of the area.

This misnomer caused Western scholars to drastically underestimate the population density of this area - until recently. This was due to numerous factors: the outdated idea that Southeast Asian populations were not capable of the complexity of building a city, and how much of the area remains under jungle and soil mounds.

The entire area covers 400+ acres and feels like a massive park with these stone buildings emerging. It includes huge water reservoirs, gateways, walkways, relief panels, and all these amazing structures. This tricks your eye into thinking “this is where the ‘city’ ends and the country begins.”

A key factor in understanding this area is a relatively new technology: Lidar. Lidar, a type of light scanner, is used by archeologists to map the subtle grooves in the land. Our human eyes would look at these with little thought as random. You use this light scanner to scan the area from either a plane, sensor, or other devices. Upload that information into a lidar map on the computer and suddenly those random grooves are street grids, building foundations, and a city invisible to your eyes. Archeologists have been using this technology all over the world for the last 30-40 years - at Pompeii, Machu Picchu, and at Angkor Wat. It’s unearthed a new understanding of the complexity of cities buried under something. It tracks the density of how light is reflected, as stone reflects light differently than a vine/plant canopy.

This has completely changed how we understand Angkor Wat and other urban areas around the world. However, a huge amount of it is still not understood by modern-day archeologists - which is the cool thing about archeology!

Restoration and the Remaining Burden from Colonialism

The restoration of Angkor Wat is riddled with complexities and issues with colonialism. It was fascinating, frustrating, and not surprising to hear about as a former museum professional.

Essentially, the city was abandoned, with just monks visiting for their own religious ceremonies. Then the French came with interest in this “temple city” and were astounded by what they found. It is literally the largest site of its kind in Southeast Asia and should get respect. The French started excavating with zeal. They started rebuilding the temples and exporting statues and goods found to Europe and America (many of which still reside in Western museums).

The French rebuilt some temples and left other temples with meticulously labeled blocks using a numbering system. Then they sorted these blocks by the numbers. However, when the French colonial rule ended, they left Cambodia quickly. They left with the documentation of what the numbering system meant, which is now lost in discarded paper records and the memories of deceased archeologists. At this point, Cambodia now has piles and piles of renumbered stones stacked in a different order than how they are found, without any map or knowledge of how to reconstruct them.

There are additional sites that were never touched by the French which are also spread around. With sites left in their natural state of half-remaining temple walls or entire stone piles, the stones fall relatively close to where they were. These stones fit together well so you also know where a frieze goes and what the height might be or where an archway is. However, with the French-touched sites, these stones are literally just in piles that don’t show any of this. It is completely reorganized by other attributes, so you have a monochrome puzzle without edges to put together. The sites with French intervention (or intrusion) are literally left in a worse state with the numbered sites than the ones that were not organized. It is a mess.

At this point, the naturally-left sites are being excavated with care and rebuilt, and they are leaving some for future generations and better technology. The French sites are getting a digital treatment: scanning every stone at a site into a digital CAD system to leverage AI and computers to digitally recreate the buildings before reconstructing them in real life (with the effort needed).

Final Thoughts

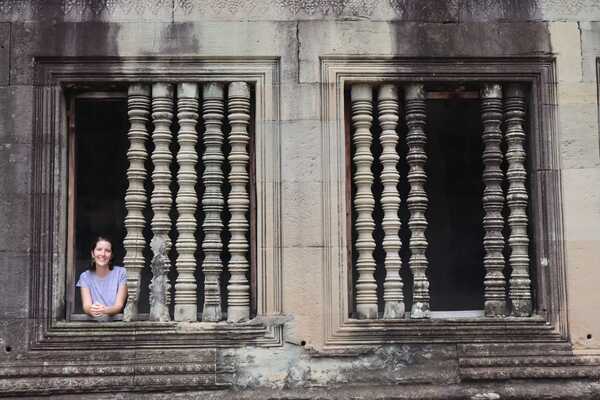

Frankly, this is one of the most impressive sites we visited. Additionally, the complex was pretty empty on the weekdays - which is really just about our timing for this post-COVID lockdown trip. Walking around, you could feel like one of the few people there and frequently find yourself as the only one in a room.

Because people are either nervous to travel to Southeast Asia or not allowed to travel yet (mainly Chinese citizens) because of COVID, Angkor Wat is empty. If you look at photos from 2019, it was as packed as a concert or Disney World. Here, it is empty. It allowed us to feel a bit more spiritual, present and connected to history. It was truly an incredible visit.

Tim and I both walked away with a question “why did we not learn more about this in our own education”? This is one of the most powerful empires in the history of the world and had the largest population center on the planet for several hundred years. It made us reflect further on how ethnocentric the American education system is, and we started brainstorming ways for our future theoretical kids to learn outside of school about subjects and things like this. Additionally, Cambodia is far from a democratic country and went through a genocide recently enough that it sits within living memory. These things are true. But there is still culture there to be celebrated, and we walked away with this feeling of “why can we not speak about both of these things? Why do we not discuss the shortcoming of its current political system and still celebrate the history of a culture that was rich and diverse?” It would give a more humanitarian lens to this population, which is more accurate to any government and society.

We have also been very impressed with the UNESCO World Heritage Site list, and have been thinking about using that to plan trips and future explorations. Alternatively, you can also use that as a way to think about major historical sites around the world as a base to teach from. These are also areas that are protected more and held to a pretty high standard for maintenance. It ends up being a negotiation between the UN and local governments to keep those areas clean, and they are flooded with tourists. This comes with complexity. That said, we have really appreciated and enjoyed these sites on every continent so far.

I think that if you can get there, you should. It is the largest religious monument on the planet. Siem Reap is very friendly to tourists and families, with most people speaking English due to tourism. And it is huge. We visited 5 different days over the 10-day stay we had in Siem Reap, yet we never were bored. I did several drawings. We did a photo shoot. We took a history tour. We explored temples less visited on the beaten path. We learned and soaked it in. And I am so glad we did.